CIM: Alaska

Portraiture, Still-life, Landscape, Murals, Itinerant Portraitist, Old Master, Oil painting, Self-Portraits, Children's Portraiture, Yale, Yale Portraits, Davenport College, Davenport College Portraits, Sterling Memorial Library, Sterling Memorial Library Portraits, Women Artists, Women Artists NY, Women Artists USA, Contemporary Portraiture, Contemporary Painting, Multidisciplinary Artist, Installation Art, Artistic Activism, Public Art, Documentary Film, Documentary Film Award Winner, Mural Artist, Animal Portraits, Snakes, Snakes Portraits, Glass Sculpture, Drawing, Art Drawings, Commissioned Artwork, Alaska Artist, Alaska Art Installation

Utqiaġvik, Alaska, and Denali National Park August 2–23, 2019

Alaska is a place of overwhelming natural beauty, with bears larger than bison, parks the size of nations, and glaciers bigger than many U.S. states. Yet the Arctic sea ice is retreating, shores are eroding, glaciers are shrinking, permafrost is thawing, and insect outbreaks and wildfires are becoming more common. My Alaska journey began in Utqiaġvik, coinciding with the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission Whaling Captains’ Convention and the celebration of Kivgiq, an international cultural event that attracts hundreds of visitors from around the Arctic Circle. Utqiaġvik, located north of the Arctic Circle, is one of the northernmost public communities in the world. The location has been home to the Iñupiat, an indigenous Inuit ethnic group, for more than 1,500 years. Because transporting food to the city is expensive, residents rely on subsistence food sources. Whale, seal, polar bear, walrus, waterfowl, caribou, and fish are harvested from the coast or nearby rivers and lakes.

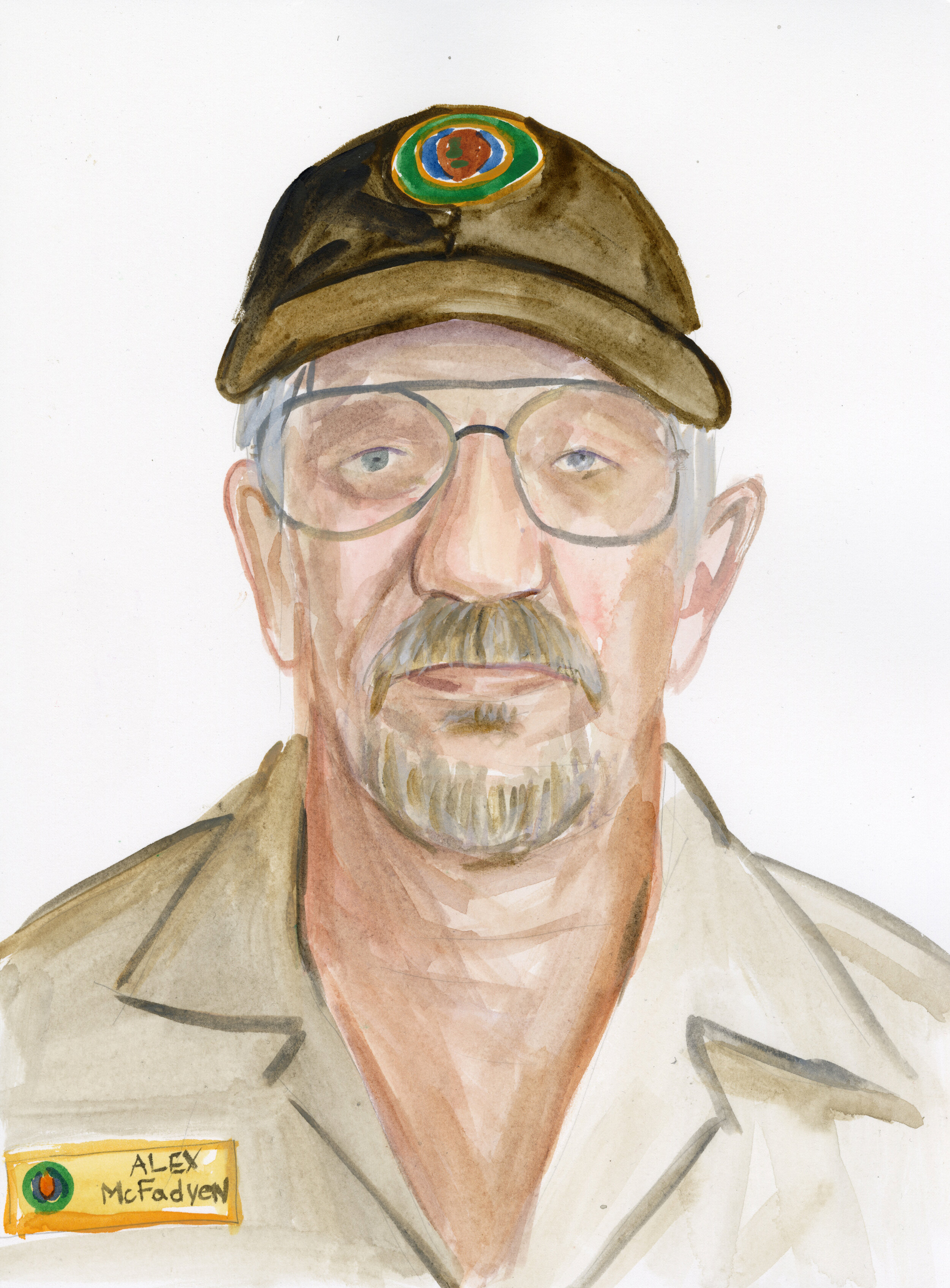

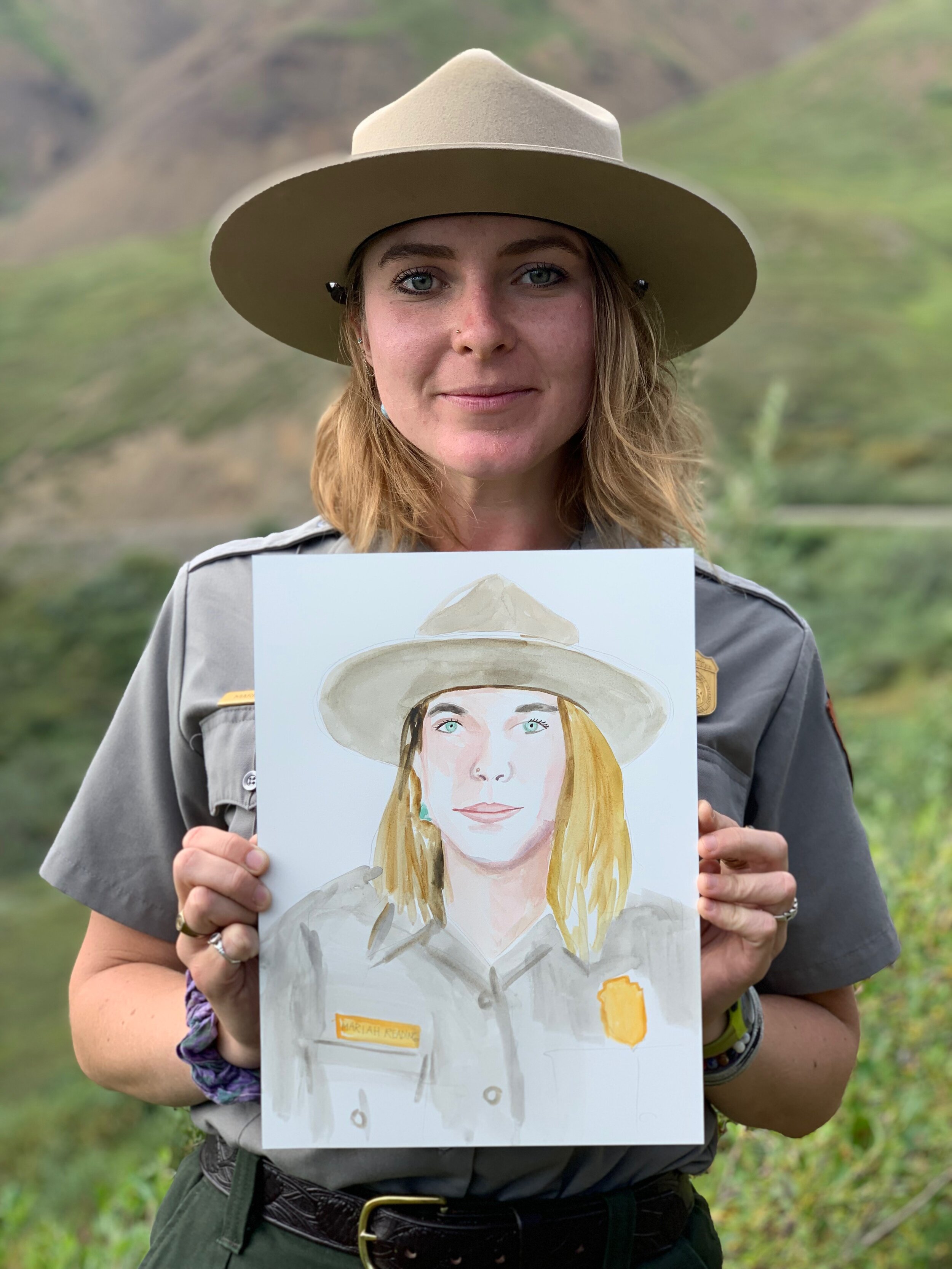

The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet. Summer sea ice in the region shrank by nearly 40 percent between 1978 and 2007. Warmer ocean currents have shortened the spring whaling season and are altering whale migration patterns, while less ice has made whaling more dangerous. In Utqiaġvik, I painted local whalers, anglers, and hunters and recorded conversations about these concerns. Before setting off to a cabin deep in the wilderness of Denali National Park, I stopped in Fairbanks for a few days to paint and interview climate scientists at the University of Fairbanks. The climate crisis was evident upon my arrival at Denali National Park, when halfway down the only road into the park, I was forced to wait out a landslide and advised to turn back. During my ten-day residency, this road was shut down several more times as a result of climate-related landslides, preventing the bus drivers who ferry thousands of tourists through the park each day from entering. For the final week of my Alaska journey, I served as the artist-in-residence at McKinley Chalet Resort. The resort’s location at the park entrance made it possible to work with scientists, rangers, dog trainers, and firefighters who could not make it into the park during my residency there.